For decades, scientists have puzzled over how Neanderthals managed to spread so widely across Eurasia—from the rocky coasts of Spain to the frigid highlands of Siberia. With few archaeological clues to trace their steps, much of their migration story has remained speculative—until now. A new study led by anthropologists at New York University and the University of Algarve uses cutting-edge computer simulations to reconstruct the ancient routes these early humans may have taken.

Their findings reveal that Neanderthals could have crossed vast distances surprisingly quickly—over 3,000 kilometers in under 2,000 years—by exploiting warmer climate windows and river corridors. These digital reconstructions offer a striking new lens into early human mobility and how environmental features shaped prehistoric migration.

Read More: 16 Chic and Functional Beach Bags to Carry You Through Summer

A Shared Past and a Diverging Path

Neanderthals and modern humans share a common ancestor, having split around 500,000 years ago. While our direct ancestors remained in Africa for much longer, Neanderthals ventured into Europe and Asia early on, eventually populating regions as far apart as Western Europe and Central Siberia. Researchers believe Neanderthals reached Asia between 190,000 and 130,000 years ago, with a second major wave occurring roughly between 120,000 and 60,000 years ago. The question that remained was: how?

Bridging the Archaeological Gaps with Simulation

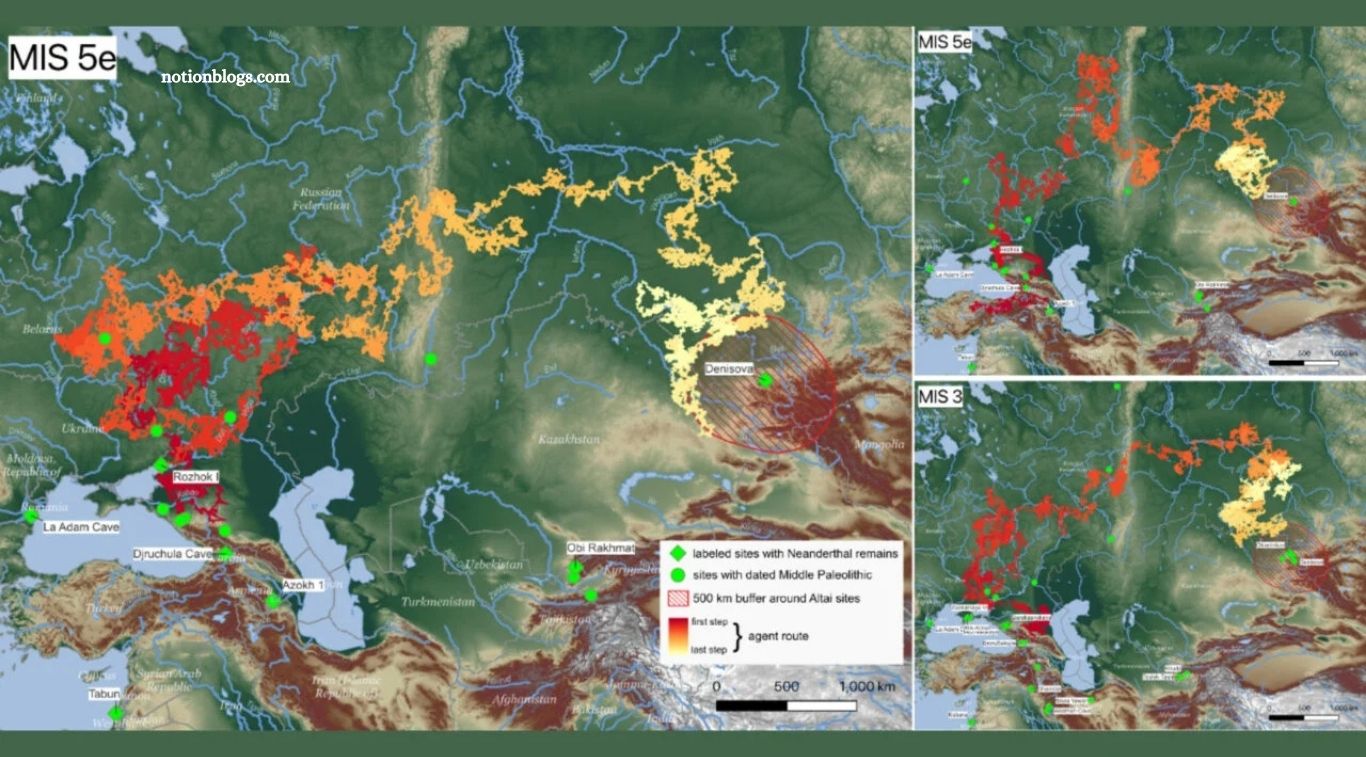

Due to the scarcity of archaeological evidence in vast stretches of Eurasia, traditional excavation methods haven’t offered a clear picture of Neanderthal movements. To overcome this, a team led by Emily Coco and Radu Iovita employed computer modeling to simulate potential migration paths. Their approach integrated variables like ancient climate patterns, elevation, glacial presence, and river systems to determine the most likely travel routes.

The results were remarkable. The models showed that Neanderthals could have migrated from the Caucasus to the Altai Mountains in Siberia—over 2,000 miles—within 2,000 years. They likely traveled during interglacial periods when climates were warmer and more favorable, following natural river valleys that cut through mountain barriers and open terrain.

Fast and Strategic Migration

Two timeframes emerged as especially viable: around 125,000 and 60,000 years ago—both periods of relatively warm climate. During these windows, Neanderthals could have moved efficiently across northern Eurasia using river corridors such as those near the Ural Mountains and southern Siberia. These routes align closely with known Neanderthal archaeological sites and overlap with regions associated with Denisovans, supporting evidence of interbreeding between the groups.

“This fast, long-distance migration had been hypothesized based on genetic clues,” said Radu Iovita, “but now, with simulation-based support, it seems to have been a likely outcome driven by landscape and climate.”

The Power—and Limits—of Digital Models

Though groundbreaking, the researchers acknowledge limitations. Their simulations don’t account for all possible factors influencing Neanderthal migration—such as vegetation, food availability, or short-term climate fluctuations. Still, in the absence of physical trails, these models offer valuable insights into how ancient humans may have responded to shifting environments.

As Emily Coco noted, this study demonstrates how digital tools can illuminate human history in ways traditional archaeology cannot. It may not be as romantic as retracing Viking sea routes by boat, but it’s a scientifically rigorous way to step into the footprints of our distant ancestors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the Neanderthals’ expansion considered “fast”?

The study shows that Neanderthals could have migrated more than 3,000 kilometers across northern Eurasia in under 2,000 years. For a prehistoric population without modern tools or transportation, that pace—averaging over 1.5 km per year—is surprisingly swift.

What does the title mean by “New Insights Reveal the How”?

It refers to the new use of computer simulations to model possible migration routes. These models reveal that Neanderthals likely used river corridors and migrated during warmer periods, making such large-scale movement feasible.

How do these insights change what we thought about Neanderthal migration?

Previously, theories were largely based on sparse archaeological and genetic evidence. This study offers a plausible, data-driven explanation for how Neanderthals could have traversed vast and varied terrain efficiently.

What technologies were used to generate these new insights?

Researchers used landscape-based computer simulations that factored in ancient temperatures, elevation, glaciers, and river systems to reconstruct likely travel paths.

Why is understanding Neanderthal migration important?

Their movement patterns help us understand early human adaptability, interactions with other hominins (like Denisovans), and the spread of genetic traits that persist in modern humans today.

Does this study mean Neanderthals were more advanced than we thought?

Not necessarily “advanced,” but it does suggest they were highly adaptable and capable of strategic movement across challenging environments, guided by natural features like rivers.

Conclusion

The rapid spread of Neanderthals across Asia, once shrouded in mystery, is becoming clearer thanks to innovative modeling techniques. By leveraging computer simulations that account for geography and climate, researchers have revealed plausible migration corridors that allowed Neanderthals to traverse thousands of kilometers in relatively short periods. These findings not only shed light on how our prehistoric relatives moved across challenging landscapes but also highlight the power of modern technology in uncovering ancient history.

While questions remain—and simulations can’t capture every nuance—they offer a compelling framework for understanding how Neanderthals adapted to and exploited their environment. As digital tools continue to evolve, so too will our ability to trace the complex journeys of early humans and appreciate the resilience that shaped their legacy.